Why the 1890s?

My grandmother was born in 1923, yet, as I noted in my introductory post, the novel is based in the 1890s. Why the mismatched timeline?

As I set out to write the novel, I was embarrassed to realize that I knew little about Cuban history. Growing up, Cuba was more of a mythical land your elders reminisced about than a place you learned about. So I went in search of a comprehensive history to get a broad understanding of the country. To my incredible good luck, a Pulitzer Prize-winning history of Cuba was recently published: “Cuba: An American History” by Ada Ferrer.

In nerdy homage to this historian, I named my protagonist Ada.

Cuba was a relatively sleepy island until the 1790s when the Haitian Revolution rocked the Caribbean (and the world). As the sugar industry in Haiti (then Saint-Domingue) imploded, Cuban planters eagerly filled the void. But, while the sugar boom enriched Cuba, it had the collateral effect of tying it more closely to Spain. As the enslaved population swelled with the rise of the sugar industry, so did the threat (and the reality) of slave revolts, and the military presence of Spain meant security in the eyes of white planters. So, at a time when most of Spain’s American colonies were gaining their independence, Cuba was stuck as Spain’s Ever-Faithful Isle.

Nevertheless, white anxiety over the prospect of a “race war” (which Spanish propaganda relentlessly predicted) was not evenly distributed across the island. Eastern Cuba didn’t depend on sugar or slavery as strongly as Western Cuba. In fact, it had a long tradition of black landownership and (relative) equality. As a result, race-based fearmongering didn’t chill the spirit of revolution in Eastern Cuba quite as effectively. It’s not surprising, then, that Eastern Cuba was the epicenter of Cuba’s long struggle for independence.

Officially, the Cuban independence movement began on October 10, 1868, when Carlos Manuel de Cespedes, owner of a modest sugar plantation near the eastern city of Bayamo, freed his slaves and invited them to fight with him for Cuba's independence. Other eastern planters followed suit. As news spread, enslaved men and women throughout the region rushed to join the rebels. While the white planters who set the rebellion in motion did not call for (or necessarily desire) the immediate end of slavery in Cuba, they soon lost control of the narrative, and the cause of Cuban independence became decisively entwined with the cause of emancipation and, later, racial equality. So, at a time when racial “science” was rationalizing racism and Jim Crow laws were cementing apartheid in the United States, “The struggle for freedom from slavery and freedom for Cuba were part of the same epic.” (Ferrer, Insurgent Cuba, 127)

Lieutenant General Antonio Maceo's cavalry charge during the Battle of Ceja del Negro. October 4, 1896.

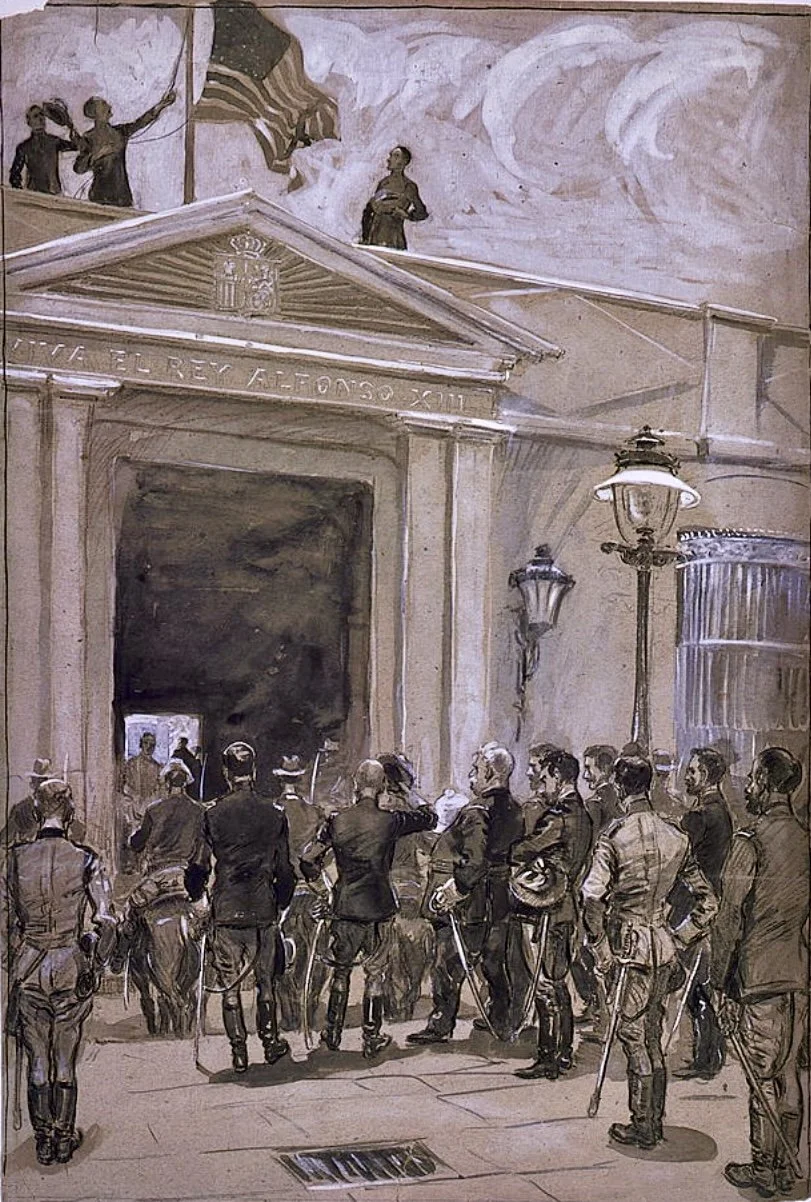

Beyond finding this all incredibly fascinating, the period of Cuba’s wars for independence (three wars were fought over thirty years) was personal to me. I grew up hearing of ancestors who fought and died in these wars, singing the Cuban national anthem, La Bayamesa, which celebrates the independence movement, and reciting the poetry of José Marti, known to Cubans as the Apostle of Independence. In learning more about the period, I was moved by the palpable sense of hope, the grand vision for the future Cuban republic with the new century on the horizon, and the sudden and anticlimactic way it came to an end, with the intervention and occupation of the United States.

So, I chose to set my story in the closing years of the final war (1895-1898), hoping to capture some of this energy. I hope my readers will find it as intriguing as I do.

Raising the U.S. Flag over the Governor’s Palace in Santiago de Cuba. July 17, 1898.