Los zapaticos de... Bala Cynwyd?

You’ve probably been thinking, “It’s been a while since Vivian has posted. I sure miss her random facts about Cuba sprinkled with tidbits of family history!”

I’m here to tell you you are not going crazy. It has been a while but for a good cause. You’ll be happy to know I’m smack in the middle (or, technically, at the quarter mark) of a frantic rewrite of my novel. I’ve given myself a tight timeline to keep my momentum going, so this won’t be a research-heavy (AKA time-sucking) post. But something kind of cool happened the other day that I wanted to share.

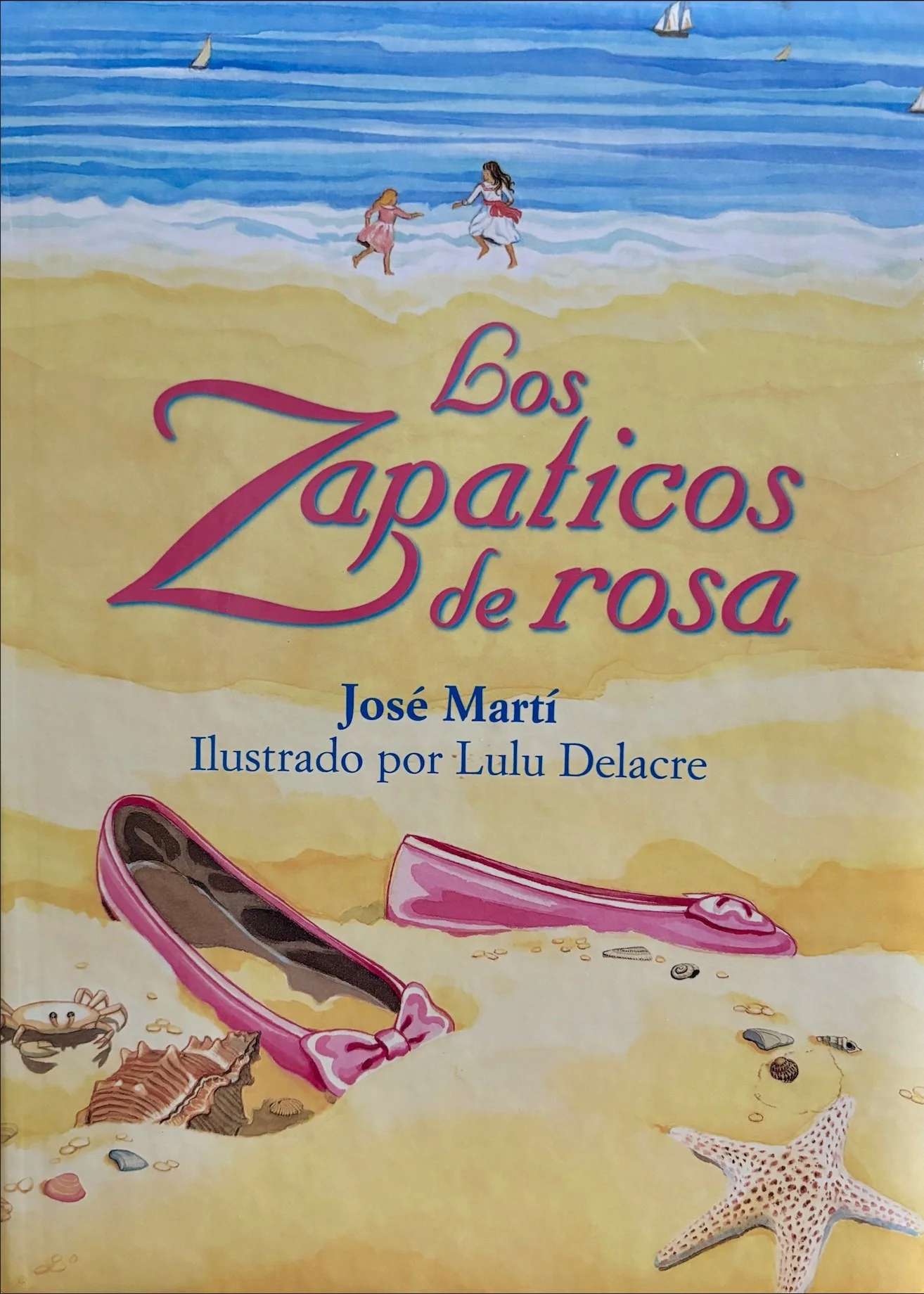

I was on a walk on a recent winter’s morning when I peered into a Little Free Library and, to amazement, saw this:

A Cuban cultural artifact surfaces unexpectedly in suburban Philadelphia

If you are Cuban, no further explanation is necessary. If you are not, I’ll do my best to explain the significance of this icon of Cuban culture.

Los zapaticos de rosa is a lovely children’s story in verse about a rich little girl named Pilar who goes to the beach with her mom one day. When she wants to go off to play, her mom warns her not to get her new pink slippers wet. Well — wouldn’t you know it? — Pilar returns a while later, completely barefoot, no pink slippers in sight. When her mom starts scolding her, a poor woman intervenes, explaining that Pilar had seen her sick daughter’s bare feet and given her the slippers. Pilar’s mother is so moved by the woman’s story and by Pilar’s act of kindness that she gives her more stuff: a shawl, a ring, a flower, and a kiss.

I haven’t found an English translation that does it justice, so you’ll just have to trust me that it’s a wonderful love-thy-neighbor-type poem.

But if you’ve been paying attention, you noticed the author, José Martí, and maybe even remembered seeing his name in this very blog.

A statue in New York City’s Central Park depicts the moment Martí was mortally wounded at the Battle of Dos Ríos. SOURCE: Central Park Conservancy

José Julian Martí Perez (1853-1895), Father of Cuban Independence, is one of the few historical heroes who actually lives up to the hype. Martí - political theorist and activist extraordinaire - was, among other things, an accomplished journalist, playwright, essayist, and poet. Somehow, he also found the time and inclination to produce a children’s magazine, La Edad de Oro, dedicated to the “Children of America” (by which he meant Latin America; sorry to my United Statesian readers) and full of beautifully illustrated poems, essays, and stories chock full of Martí’s signature idealism. Only four issues were ever published, July-October 1889, each 32 pages long. I’m tempted to research why the magazine was discontinued, but that may lead me down another Google rabbit hole, so if someone figures it out, please let me know.

So what was this most Cuban of books doing in this decidedly not-Cuban suburb of Philadelphia? The only reasonable explanation was that it was a message (of encouragement, I hope) from my grandmother, from the great beyond!

My cynical children rejected this explanation as “ridiculous” (while presenting no credible alternative). So I called my sister, who believes in all the things. When I told her the story, she immediately reached the same conclusion: “It was Mami!”

She reminded me that it was my grandmother’s favorite poem (ok, so this might apply to 99% of Cubans), and she often recited it from memory (ditto previous aside). But she also reminded me that my grandmother always lamented that her own mother abandoned her when she was sick while the poor mother in the story took care of her child no matter what.

It was a good reminder of why I set out to write this novel in the first place and helped me rededicate myself to the project right as I was preparing to launch into a full-scale rewrite.

Coincidence?